What’s the point of schools any more? Kids are socialites at 7, adults at 12 and doubting everything the teacher and the school stands for. Behaviour is questionable, deference is a quaint notion of a rose tinted past when teachers were head of the classroom and everyone knew and welcomed their places.

Curriculum is irrelevant and has been superceded by the Internet where children work out of their own curriculum and syllabus, perhaps blindly, perhaps intuitively, perhaps guided by who knows what – certainly things we parents and teachers know nothing or little about.

These are desperate existential times when all our purposes reasons and rationales have been thrown up into the air and scrutinised like never before. So what place the teacher? The school? The curriculum even?

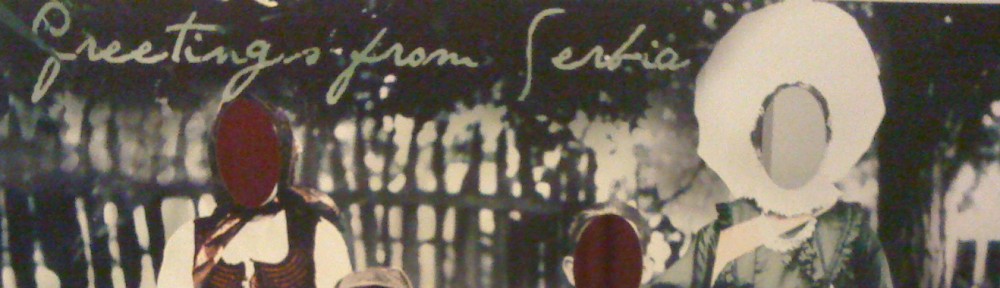

For all that despair and deep questioning…there is still the essence of the adult / child relationship at the heart of the learning process – the adult / old knowledge can’t be swept away. There is history -culture – language – the other – to contend with.Stuff which resides in the old, the unfamiliar, the awkward, the stuff the young don’t / won’t access drily through the Internet and the fashionable modes of social networking.

What we are left with -.and what can’t be swept away in a tide of acronyms and text speak – is us – you and me here and now in real time and space and our awkwardnesses and misunderstandings.

What is the point of school, teachers, curriculum? To learn of the other, from the other; to socialise the unsocial and antisocial; to expose our awkwardnesses and differences and to acknowledge, value and celebrate difference and otherness.

This is not just about engaging in extra-curricula activities. “The other” in this context means anyone who is not like us; who has different knowledge bases and skillsets, different languages and different habits and cbringing this means bringing different subjects and knowledges to the student through the essential relationship that students have with their teachers (and peers and families etc).

School has to be about bringing us close, again, to people ‘not like us’ – who we might deem unacceptable, troublesome, problematic as they don’t fit our world view. This is more than just going to art classes but meeting new cultures, ways of being and different socialities than we are accustomed to. Again, all matters which can be brought to bear by rigorous, challenging educational content: and certainly not just through ‘hanging about with your mates’ at the end of a long hard school day.

The point of schools is that they have to provide spaces, relationships and time with teachers and peers to bring all those matters to the fore. Whether our schools do that at the moment, again, is another question that needs asking. No amount of befriending on facebook or googling the worlds ever expanding databases will ever be able to emulate the simple purpose of education and all its actors: the ability for me to understand you and you to understand me, in all our differences, three dimensional truths and multi dimensional complexities.